I

I’m still waiting for the day suits will start fitting right on me. The day I knock on a customer’s front door and they don’t look me up and down like a kid in dress up. Boxy shoulders, sleeves hanging to my knuckles; I’ve begged Monty Jones to show me he how he does his tie every Monday since I started at Loveridge and Jones.

He comes up with a different way of explaining it every time: Rabbit hopping home to the burrow, ship rope around the head mast….and still…I look like a school boy rushing to his senior formal, every shift I head out on.

Ma’s work attire never looked out of place. Her hair was pathologically clipped just so, not an ounce of lint on her power suit to be seen. Even after a full night’s work, she’d come home looking like she’d just popped out to a health retreat for the moment.

Ma will forever be thought of as a wise lady around town.

You wanna know why? She died at age twenty seven.

Not that there’s anything wise in dying young.

No. The reason she’ll forever be remembered as wise is… well…we’ll get to that point soon enough.

Those same townsfolk who revere my mother will never talk about me in that way though. No wise guy label attached to Henry’s name. I can’t believe I’m already seven years deep into the wasteland my Ma never got to see. Thirty four.

Shit Ma, wish you could see the view from here…

Sure she did well with the time she had. But I coulda said the same at twenty-seven as well. Thirty four is a whole different briefcase of product to sell.

Kim’s pregnant again. She overheard them gossiping about it in the break room at her work on Tuesday. Heard them say the only three syllable word you’ll ever hear out of their hick mouths: “Hypocrite.”

Knowing they learned that word specially for us, doesn’t make it land any softer.

At least we’re married this time around, but would you think that makes an ounce of difference to them?

I suppose one thing Ma had on me at twenty-seven, were the kids. You got me there Ma. I enjoy the benefit of seven extra years and a partner to share the load with. God only knows how you did it alone. Alone, with a full time job. Alone here in Tridell? Alone, here in Tridell in the fifties?

Even now I’m questioning why I’m about to raise a second child in this place. One’s proven to be more than enough.

And that’s not to say that Kerry isn’t a gift. She is. Truly a gift.

The type of gift you wouldn’t necessarily buy for yourself per say. Like sky diving lessons or a trip to the Congo. The type of gift you only use ‘cause you know how much they probably spent on it. But then you end up really liking it. Truly. You end up liking it because you know how much they want you to like it.

No—that sounds ungrateful. When Kim first told me about Kerry—about six months into our relationship— I was looking forward to meeting her as much as I’m looking forward having one of my own. Truly.

Anyone from the big city reading all this talk of struggle and wisdom, is probably wondrin’ just how crooked our small world lives could really get.

Between the corner pub, the post shop and the Saw-Mill, who’s throwing down all these thumb tacks and banana peels on me and my Ma’s path anyway?

I understand that typa thinkin’. Sure we might not have big business worries. No, the stock prices ain’t about to crash down on anyone’s head here in Tridell. But we’ve got our troubles, and they scrape just as nasty as any big city crisis.

Ma, worked as a Loveridge and Jones employee from the day the company registered its ESTAB title right up till the Monday morning they stamped an end date on her death certificate. She worked the same beat I walk, for over eleven years—boot of the car, briefcase, hipflask for the harder nights—no gear stick for me to wrestle with on the way out there, but not much else has changed.

Rural folk don’t take kindly to being slung to as a rule, and when you’re slinging the L & J prescription?…not much has changed.

The city folks would tell you, my clientele are the ones who need it the most. And no it’s not lost on me that their reasons come from a place of hate, a place of thinkin’ a Tridell life is worth less than a New York one, but that doesn’t make ‘em wrong about the broader point.

Folks around here do need L & J more than most.

Most of ‘em are already financially strained before they pop out a kid, most don’t have the education or discipline to lay off the drink till they’re due.

And deep down, they know it themselves.

These same folks barricade their daughters inside cold homes after nine pm every night. They’re the types to have a side-by-side Winchester specially set aside for marital encouragement.

Don’t you try to tell me that’s not on account of some type of instinct. Those fail-safes are there for a reason!

But, oh no. Their lord and savior will never let them take the direct route I’m offering with my L & J prescription. At least they’ll never admit they’re willing to take it…but my business is doing just fine.

The wildest thing about the “wise” Miss Crimelda Radford—my Ma— is that she used to think just like them. In all the years she was on the job, she never quite let go of that old way of thinkin.’

“I would never use the stuff personally, but I want to make it an option for those in need.”

Musta made every night on the job a blight of guilt. I guess that’s another reason why she’ll always be seen as wise, and me, not so much.

The L & J course works like this, take one pill on every day of the week that has a D in it, one for every month that includes a J, and you won’t have to worry about meeting a little Henry or a little Kerry for the remainder of that calendar year.

Go crazy sweetheart. Prom night, keg parties, bachelorette parties, divorce parties. No need to fear that nine months of build up to your eighteen years of poverty.

Now, the L & J can’t help you with the other afflictions you might find among truck stops and the back seats of cars, but it’s got the main one covered.

Yet…

In all the break rooms, all the barstools and the supermarket isles around town, L & J is spoken about in the same way meth is spoken about and just like meth, the same ones warning against it are usually the one’s eating it up nightly.

They mighta learnt the word Hypocrite just for Kim and I, but that ghost has had a hold on this town at least as far back as my Ma’s disappearance.

They call it murder. As if throwing your fingers down your throat and spewing up those seeds, is any different to deciding against eating the damned apple in the first place.

They look down on murder. But when it comes down to it. It’s just murder of their own they’re concerned with. Murder of their image. Murder of the illusion that they’re pure. Otherwise, the people of Tridell ain’t no strangers to killing things.

A woman knocking on doors nightly is playing more than one game of numbers. Every “no” gets you closer to the “yes.” Every “yes” comes from somebody who led with a “no.”

The other game of numbers is tied to that three syllable word. Hyp-o-crite. How many have a problem with “violence” publicly, but when no one is looking…

Tonight I checked in on Kim three times. She was due yesterday. I know it’s just an estimate. But estimates and averages are the only thing that keep food on my table.

It’s cold out. I decided against the puffer jacket when the clouds broke. It was a mistake. The type of mistake “wise” Miss Crimelda never would have made. I didn’t pop onto Kerry’s room outa fear of wakin’ her, pecked Kim on the lips though and stepped out into the night.

II

May as well have stayed home for the first half of the shift.

Nothing to show for it. I reached an old hoarder house on the edge of town at the top of the hour. I was on a retrace beat—for those outside the biz, that means going back to the houses I haven’t had a hit on lately. Low percentage stuff.

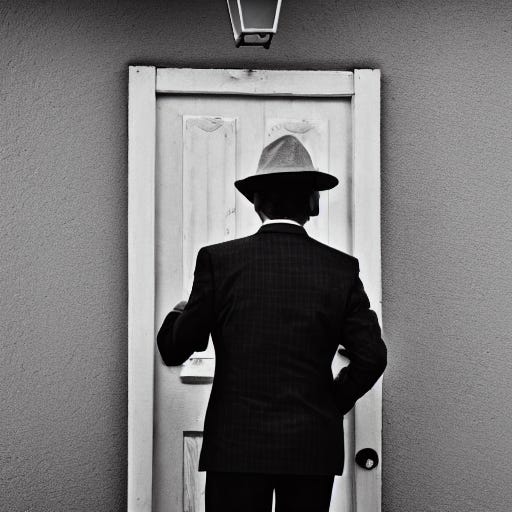

This paint-chipped, boarded up mess of a place didn’t give me high hopes. I gave its front door one knuckle rap, rather than the usual rap, rap, raprap, rap,rap. Mainly because the moss on that door looked suspiciously asbestossy.

You can only imagine my shock when a rosy cheeked face appeared in the doorway a moment later. Big, intelligent eyes—familiar eyes, a tidy fringe and a god damned power suit of all things! The woman’s contrast to her surroundings looked like a bad photoshop job.

“Can I help you?”

I had to blink away an irrational thought. For a sec there it sounded like my Ma—and those eyes, they were Ma’s eyes.

But no. Far too young. She wasn’t as tall as my Ma either.

“Ah yes, Ma’am.” I cleared my throat and tipped my hat as I remembered where I was. “M’name’s Henry Radcliffe.”

“I know who you are Henry—”

I squinted a bit harder at her face. Remind me to get my eyes checked one of these days. Vision’s goin’ to the dogs. “Sorry, M’am for my rudeness, but I can’t quite place you…”

“I know Crimelda.”

I felt sick and suddenly found myself rechecking the boarded up windows and stacked boxes of junk in the hallway behind her. “This your place?” I asked, taking a peak past her shoulder.

“I’s baptized here. But never truly got a chance to call it my own.”

That’s usually the cue. Bible reference, scripture, practice, anything down those lines; it’s their polite way, or at least the Christian way of saying, “I’m not your buyer, guy. Try the next house.” I started to turn.

“Crimelda has a lot of respect where I’m from.”

I sneered. “Clearly you’re not from Tridell then.”

She caught my arm. I looked down at her oddly warm grip despite the chilling night. She stared at me with an intensity that mades me want to get back to Kim and the kids immediately.

“Henry, do you really believe that’s true? You don’t think the people of this town hold your mother in high regard.”

Again, with the present tense. Lady, my idea of “believe” is very different to yours! I felt like saying. Who was this woman speaking as if my Ma might pop around the corner at any moment?—and talking in such familiar terms. A heat started to surge in my chest and I shook her hand away.

“Oh, they’ll praise my Ma to high heaven. Wisest woman they ever met. But that ‘respect’ didn’t stop them talkin’ when she was around. That respect’s real easy to give after the fact!”

“After what fact?”

I closed my eyes and made a real point to inhale. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. This non-local digging into places she had no business. Probing me on a subject I hadn’t even breached with Kim yet. That warm hand touched me again, a second brushed my lower back.

“Henry, after what? What do think happened to your mother?”

I was shaking, no trembling. I couldn’t open my eyes—too afraid of what might happen if I looked at her face.

“Henry, I want you to come inside with me. If you can’t talk, I want you to listen.”

I didn’t talk. But I listened.

III

I glanced down at my shoes. The laces were tied, but strung loose from where I’d opened up the tongue to fit my sock in.

“Back when your mother was on the job. Times were harder…”

“Oh, don’t I know it!” I rolled my eyes and started looking for the door. The couch I was perched on the edge of—so as not to get my suit dusty—was an old leather thing that might have been comfortable once upon a time but now had stuffing and springs poking out from all angles.

The lady started across from her single seater—one of about a dozen chairs that had been dragged around the couch in a semi-circle who knows how many decades ago. Who knows how many squatters ago?

The way she stared wordless made me hopeful for a moment that I’d finally got her on the back foot, finally knocked some of that self-assuredness out of her. But there was somethin else there. She was looking at me like I was half a coin short of the bus fare.

“Henry, you’ve got to remember the times Crimelda was living in.”

I rolled my eyes. “Oh yes, sorry, I forget about Tridell’s liberal renaissance…things are so progressive around here these days.”

The woman ignored me, “Crimelda would never have been able to operate in this town had the Tridell locals not recognised she was one of them at heart.” She raised her eyes to the rotten overhead beam and spoke fondly. “Your mother was like a reverse Jehovah’s witness. She’d turn up to a door and they would preach to her! Unlike you, she’d actually listen…”

I rolled my eyes. “Yep, and let me remind you, it almost drove her to the brink.” I shook my head. “If those barbarians failed getting to her in the end, I’m sure the guilt would have.”

The woman wagged her finger as if she hadn’t heard me. “Crimelda was always good at giving it back mind you. Never short on a scientific explanation, a clever anecdote as to why a one size fits all prescription could never suffice for this complex topic.”

This time I was warmed somewhat. I released a genuine chuckle and followed her eyes up to the beam. Old oak—probably centuries old. “Yea she was like a computer with that stuff. I used ta say, she had the hardware of a conservative loaded up with the software of a liberal.”

This line made the woman’s expression fall. She shook her head and her voice lowered, “And that type of duality can never survive for long in a town like this…”

I frowned and watched the woman’s eyes go somewhere else for a stretch. Eventually she returned and was smiling again.

Growing clear eyed she bounced her shoulders. “In any case, the conservative streak won her over.”

A pang of pre-simmered anger rose up before I could catch it. “What do you know about the end?” As if she could just brush over that point like it was nothing. Spit a matter of fact line at me like that as if all was understood. I felt tears begin to well. Actually well, then spilled onto my pin striped pants.

“I wish my Ma was daft enough to give in to those hicks. To let the conservative side take over. If she’d done that, she’d probably still be here!”

“Henry. Don’t you get it? Crimelda is still here!”

IV

The woman waited until she could see the colour returning to my face before lettin’ slip what she’d been holdin’ back.

”I assume you know about the birth?”

“The what?”

The woman’s expression hardened. She looked around the dust covered room. Old couches—cabinets and cupboards with sheets strewn over them—one bedside table next to the far end of the couch, covered in steel instruments I’d seen before but hadn’t let my mind focus on. I winced and looked away.

“Though she told them all the right things: I’ve got a family history; The Radfords ain’t built to give birth; A hospital might be better—” The woman looked up at me. I saw pain in her eyes. “She got scared Henry. Who wouldn’t? Started speaking beyond the birth: I don’t have the family structure to support a child; My husband’s not around anymore; I won’t be able to care for another baby.”

Though the woman’s voice didn’t adjust even slightly while she was doing her impression, in my head, Ma’s voice made it’s statements in all her former stubborn glory.

The woman swallowed a lump. “The locals—had all the requisite answers waiting for her though: God didn’t put maternity wards on his earth when he built it; The natural way is the divine way and there is no sin in adoption; The Tridell community will take care of things; We will care for this child as one of our own. If anything goes wrong we’ll care for your child.” She extended a finger my way. “Like one of our own.”

I scoffed without an ounce of humour. But the woman moved on as if afraid to neglect getting to the point now, might mean never getting to it.

“Of course as Crimelda predicted, the birth had complications. She lost blood.” The woman’s eyes strayed to the upholstery beneath my suit pants. I didn’t dare look down. “God took her early, but the baby survived.”

“Those bastards!” I rose to my feet. looking around as if I expected to see the usual suspects right there in the room with us. “So, I was right. They did murder her! And what the fuck happened to that baby? My brother, my sister…” I almost choked on these words. “They murdered her. Maybe not in the way I thought they had. But it’s all the same. With their pointed words, their empty promises, their principles which fall apart the moment they’re called to action. This town, is, was, will forever be—”

“No Henry. Their words were not empty and your mother’s sacrifice wasn’t in vain,"

I looked over at this woman not believing someone like her could even exist. I got even hotter around the collar when I realised I still didn’t know her name. “Are you kidding? How can you relay this story in one breath—then continue to side with those…those fucking neanderthols in the next?”

“Crimelda’s wisdom that day, the wisdom she imparted across those entire nine months, taught a lesson to this town.”

I was out of eye rolls by this point. “Arghhh spare me. I’m out on the Tridell road every night. I see the way this town looks at me. Judges me, judges my family.” I raised a finger and mocked, “Though they’ll remind me every day how much they respected my Ma.” I shook my head and scowled. “What lesson did they learn?”

She winced. “It may not seem like it. But the people of this town…they really do respect your mother. They recognize her sacrifice was something beyond them, divine in some ways….”

“Don’t you attach your Christian mumbo jumbo to her name. She was a logical, intelligent woman of science—”

“She was a martyr for Tridell…whether you want to hear it or not. She didn’t die on the cross of your new ideas any more than she died for maintaining the status quo,” the woman raised her eyes at me and was smiling. I don’t know how, but somehow that smile didn’t even come off as condescending, not in the usual “Christian” way. She carried on, but I was only half listening as that smile hypnotized me. “Of course their Dogma will never allow most of them to admit it. But these people learnt a lesson from your mother. Her death turned a mirror on them and forced them to face the sin of their lives, forced them to dissect where the true purity lay…and while it may not seem so. They fact that you are able to walk this town’s streets every night, selling your product. It’s a recognition that your way of looking things has its place.”

I shook my head “Sure, sure. And in ten years I’m sure this town will be voting blue and spouting gun control.

I stood up and kicked at an overturned teddy bear that would never be held by tiny fingers. I didn’t want to say it. It was looming over me, looming over this room. My entire childhood. My own family. But she kept speaking.

“Mock it all you like, but for those who need it, the L & J prescription is now an option. This was never about turning over the whole apple cart, it was about adding a few more fruit to Tridell’s table. You’re probably still too young to recognise the wisdom in that—”

This was too much, I left the room. Started making my way down the hallway. But then stopped myself when the image of that Teddy bear and that woman whose name I hadn’t even learned, wouldn’t leave.

I turned around and while still in the hallway, the words that hadn’t escaped me, finally found a way out. “What happened to the baby?”

The room was empty.

Well no. The couch, the circle, the sheet covered furniture and the surgical instruments were all still there. But the woman wasn’t in the room.

I’m a man of science, so I will not condescend to you any knowledge of how I knew this. Call it intuitive, call it Crimelda’s wisdom. But I knew.

The woman only ever spent a few minutes in this room, and that was over twenty years ago.