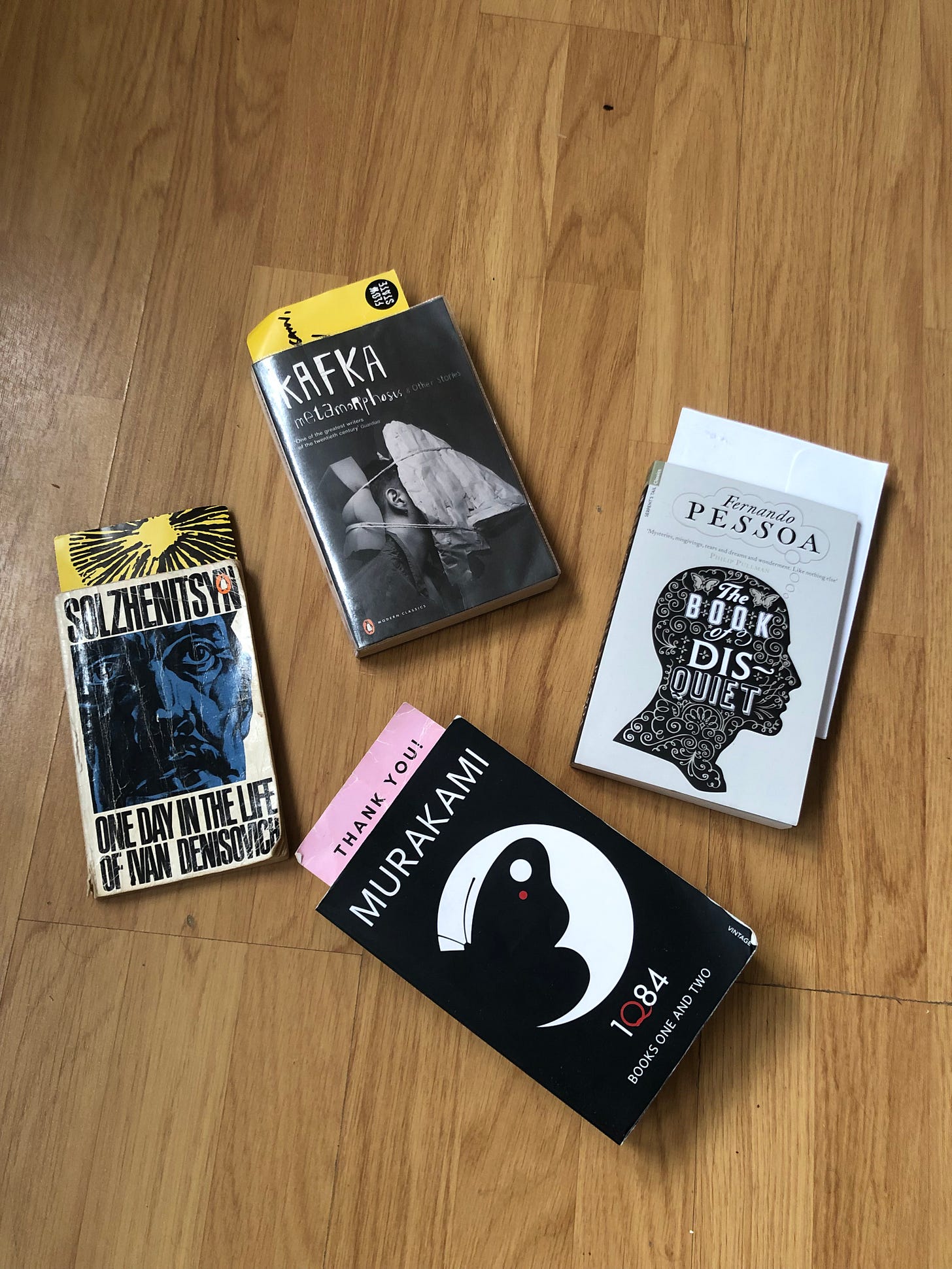

I opened my laptop this morning with the intention of writing about the five books I currently have stacked on my bedside table. Yep, I’m one of those readers. It takes me months to read a book—partially because I’m dog-slow at reading—but mainly because I fragment my reading time so dramatically. I can’t just stick to one book. This isn’t to say I don’t select what I read purposefully; I just don’t take a very efficient approaching to the reading itself.

In any case, as I was taking the above photo I was struck by the cause-and-effect that led these books to end up on my current list. It dawned on me that a much more interesting subject lay in wait here: How particular books find you, and how particular authors have a strange way of elbowing themselves into your life whether you like it or not.

Every book here has a strange not-so-coincidental connection to my life (which I’ll get to in time) but since this newsletter is named “The Sudden Walk,” it’s only natural to start with “Metamorphosis” and Kafka himself.

I’m not sure if it’s reflected in the short stories I’ve posted on this page so far, but Franz Kafka has acted as a huge influence on the novel I’m currently working on. The creepy thing about this is, I started writing the novel before I’d even heard his name or read any of his work!

Before you roll your eyes I’ll walk that statement back a few strides. I’m not alluding to any spiritual, beyond the grave stuff here. I mean, Kafka’s influence has permeated the culture to such a degree that I picked up on his lead without even knowing it came from him. Think, a kid who assumes their guitar playing is derived from AC/DC, without realizing that it all stems from Chuck Berry. Or a Stevie Ray Vaughan fan channeling Jimi Hendrix etc.

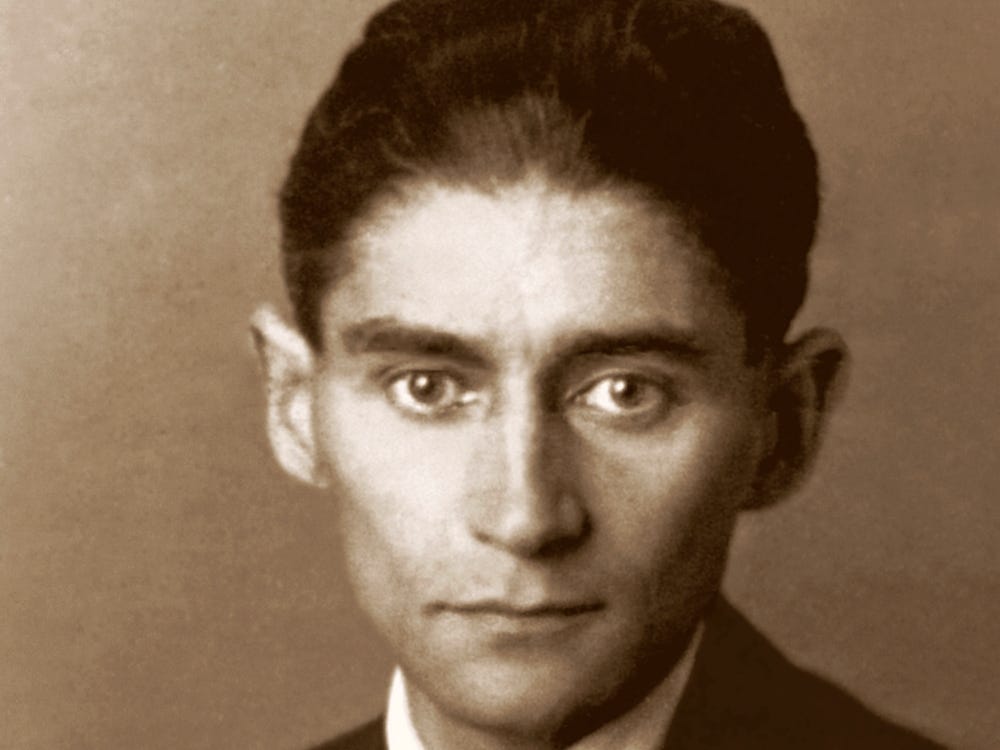

So, who is Franz Kafka?

He’s a Czech writer whose work went largely unrecognized during his lifetime. He died of TB at age forty. On his death bed he asked his best friend to burn all his unpublished work (a request that was thankfully ignored)

As it too often plays out, Kafka’s writing went on to become world acclaimed well after he’d been buried. His style, termed “Kafkaesque” tackles odd, nightmarish scenarios where an individual is pitted up against an insurmountable machine of bureaucracy and/or surreal compliance by his peers. This was eerily prophetic of the post-world-war-two years his country of birth would soon bear witness to under soviet influence.

A lot of David Lynch’s films reflect Kafka’s feel. For books, Murakami is a good starting point.

Kafka worked a day job at an insurance company for most of his adult life—something which he was reportedly quite good at but was the source of huge resentment for him as it stole so much time away from his real love, writing.

So how does all this resonate with a farm boy from Raetihi, who grew up about as far away from early twentieth century Czechoslovakia as you can get?

Boarding school—definitely not on the same scale as an authoritarian government. But all the ingredients for the Kafkaesque are there:

A closed environment, which you’ve got no reasonable means to opt out of.

A detached top-down structure that dictates most of an individual’s daily life.

Before I get too deep into this, I want to preface, that this isn’t a cry of oppression on my part. I wouldn’t trade the experience for anything if given the chance to rerun things. The insights into human nature and systems were invaluable to me. I just want to express why it resonates.

I should also mention that I played my own part in the Kafkaesque experience I had at boarding school. To be frank, I was a little shit. Breaking rules for the sake of breaking rules. Resisting with bared teeth and white knuckles any time I bumped up against a lever that even resembled an attempt to “shape” me into what the school deemed a model student. This all resulted in my larger than the average bear share of punishment; a lot of time being “disciplined” rather than enjoying myself on nights and weekends, but those aren’t the parts that stood out.

It was two particular lines that were voiced to me during that time that cement this period as Kafkaesque. One was from my first housemaster (my year group went through five housemasters during my time there, but that’s another story) when I questioned him on a rule that simply didn’t any sense to me. He said,

“I don’t’ agree with most of the rules here, but I’ll enforce every one of them.”

To me, that is the epitome of somebody serving a system over human logic, and it came from someone who was self-aware enough to recognize the illogic of what he was doing.

The second line came form the “head of punishment” himself. How Orwellian is that title? Jesus.

After I was suspended for the second time. (I already said it, I’m not an innocent party in this!) my four accomplices and I were all plucked from our various class rooms and interrogated separately.

Naturally, it didn’t take long for the powers-that-be to establish how full of holes our cover story was. But, having seen one too many gangster movies, I looked the head of punishment in the eye and stuck to the script that my mates and I had agreed on.

“You’re a coward for not owning up to this,” is the response I got.

To this day that brief exchange is still seared into my head.

Of all the words to reach for. “Coward?”

“You’ve wasted a lot of our time.” Yes. Shit even an accusation that I’m missing a few screws for failing to see the hopelessness of my situation would make sense to me.

But cowardly?

What living, breathing human being can realistically consider folding under interrogation by a (clearly hostile) institution and ratting on your friends as the more noble option than holding the line?

To me. The ability to voice those words reflects a mindless operative who is incapable of seeing outside of the machine they’re wrapped up in.

Anyway, that’s Kafkaesque for you ladies and gentlemen.

So the book….

I didn’t even hear the name Kafka until I was twenty five. I understand why I wasn’t handed it at high school, but I studied literature and history (with a heavy emphasis on both world wars and the cold war) for god’s sake. How did I avoid encountering him there?

I visited the Prague in 2017—still managed to duck him.

Kakfa first entered my life, via a video interview with author, David Foster Wallace. If you’ve ever heard DFW speak, you’ll recognize his ability of throwing out obscure names with an air of “obviously you’re familiar with this person” so even that didn’t ring as hugely significant to me. But it was enough to plant a seed.

The next seed came from one of my band mates. I came up with the below riff, and asked him to put words to it.

Click here for audio (I swear it's not a virus)

He came up with the following.

Weird subject matter out of context. So I asked him about it. He went on to explain who, Kafka was. What his work was about. Suddenly some wires touched and the name rang as familiar. I was intrigued.

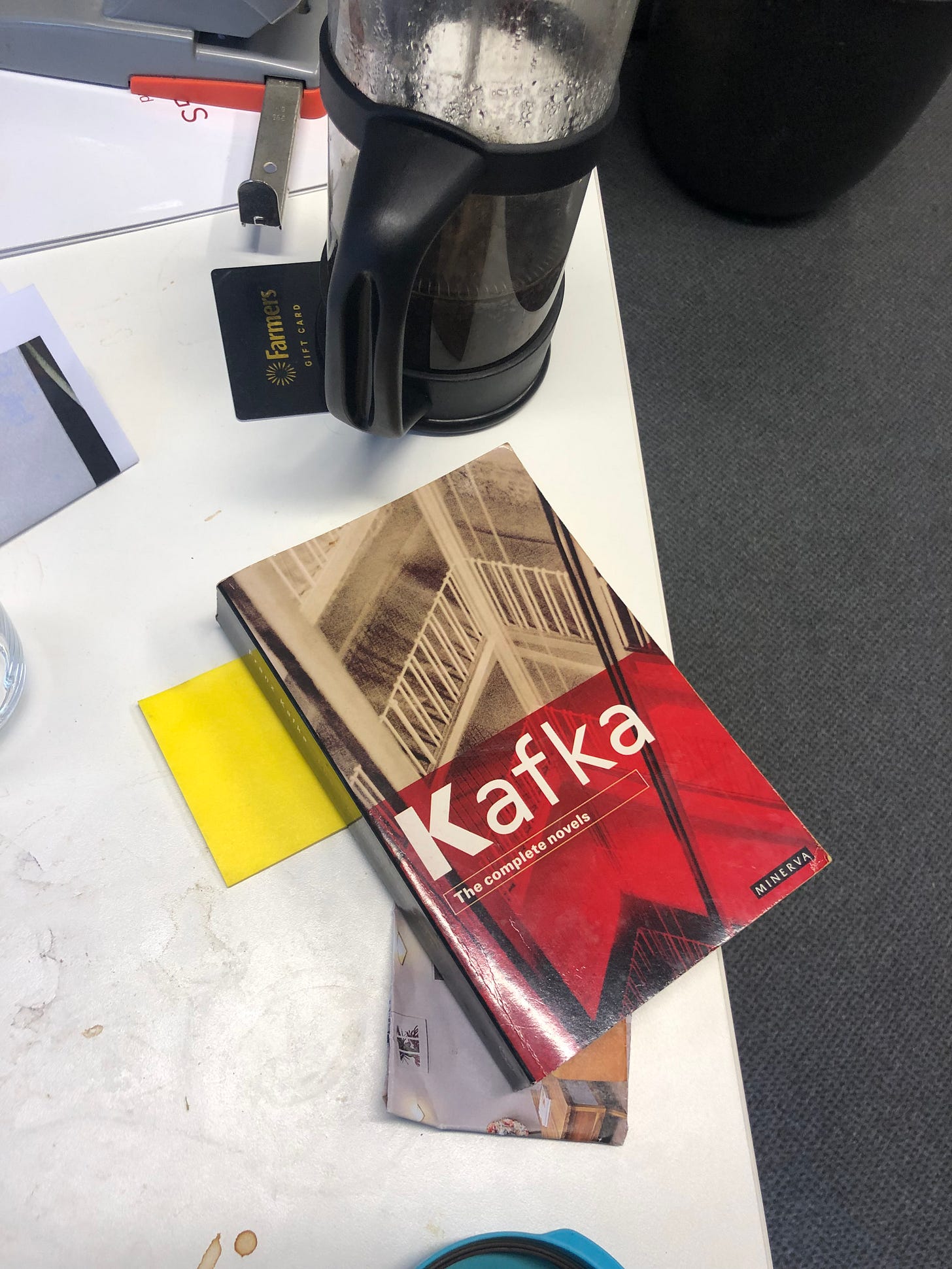

Soon after, I was walking by the used-book store next to my office—which had a below ground site with windows at foot level where they put all of their new stock. What should I see?

Kafka’s complete novels.

It was surreal to read these stories when considering the writing I’d already been working on for a good three-and-a-half years by this point. Of course, his version was much better than anything I could hope to come up with, but if I can stretch my earlier metaphor, it was a bit like my experience “properly” listening to the Beatles for the first time. I’d heard music that was heavily influenced by them my whole life (and It’s not like I avoided the Beatles’ back catalogue entirely) yet, when I finally sat down to purposefully listen to the source, there was a coming home sensation. This has been here all along, but it only makes real sense now.

That’s the strange nature of books. There are too many of them out there for an individual to possibly read them all. Even if a book or author speaks directly to your personality, you are required to identify it (or stumble upon it) before you can unlock what’s hidden within. Yet, I get the sense that like Kafka, if it’s the right book, it will find you…eventually.