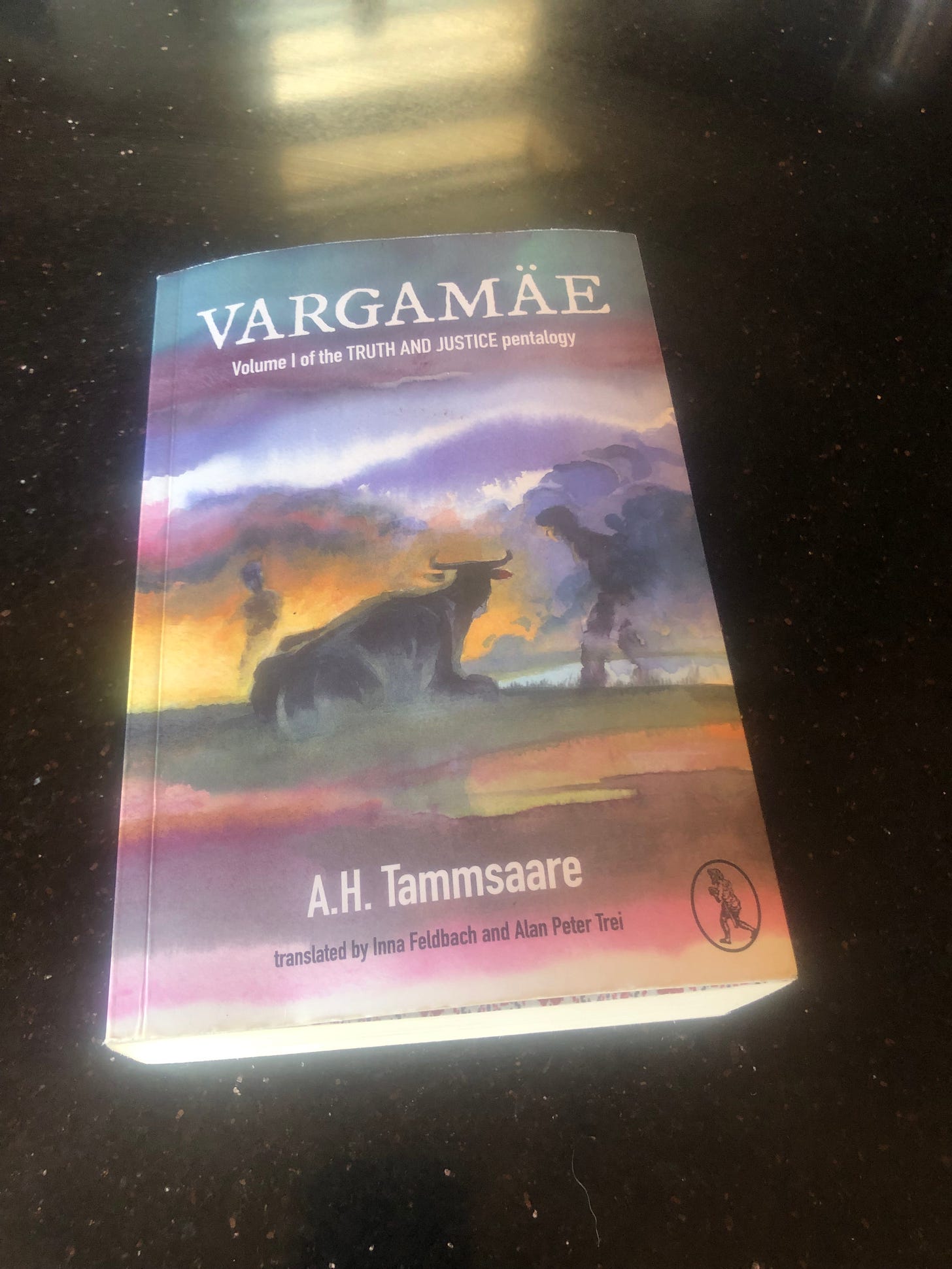

Over January/Feb, I read a book called Vargamae. It is volume one of an epic Estonian series covering the late 19th to early twentieth century.

While travelling around Europe, one of the habits I’ve picked up is googling the top writers of whichever obscure place I’m going to and finding one of their great works in a local bookstore. Vargamae was one such book.

For a tale set over a century ago in a country on the other side of the planet, the relatability of Vargamae is stunning.

It follows the struggle of a young farmer and his wife, trying to break in new land and make it into something they can be proud to pass on to their sons.

This ambition forces the couple to put their personal happiness aside in pursuit of the dream. While his mischievous neighbour lives in the moment, taking only what falls on his plate, our hero focusses on the long term—the potential rather than the immediate.

When his neighbour capitalizes on a new trend of growing potatoes and makes a quick fortune, our hero abstains, knowing that growing potato crops will ruin the soil quality after a few seasons.

But this policy of delayed gratification never pays out its investment. By the time his son nears the age of taking over the farm, while somewhat improved, the conditions of the land have not moved so far from the state the father originally purchased the farm in. Always new drains to dig, always damp land bogging down the livestock. In this time his first wife worked herself to death and his second lost the easy smile that was once her defining trait. On top of this, this son has lived a whole life witnessing the struggle of his father and wants no part in it.

Ultimately it was all for nothing and the farmer would have been better off living in the moment like his neighbour. Taking what came to him rather than trying to create more from his position.

This isn’t a cautionary tale, or some drawn out life advice piece however. The wider point made by the novel is that for this character, that living-in-the-moment version of existence was never available to him. For certain personality types, for certain minds, you have no choice but to live in a certain way. The long term, dreamer quality was always going to bind him. So it’s not so much a question of changing your approach in an unfriendly environment as it is changing your environment to align with this default position.

If he’d understood this truth, the farmer would have been better served to sell that farm and find some project where that concrete work ethic would have bore him fruit.

Another highlight of this novel is its exploration of selfish self-actualization or at least the pursuit of it. The novel captures the joy of diving into an obsession and letting all other elements of your life fall to the wayside. You see this in flashes where some of the hardest moments draw out great happiness from the main character. The comradery between he and the other farmers in their shared struggle is one the woman and children never get to share.

The tragedy of this approach in the novel is it’s impact on the children’s perception however. Because the father cordons off those different elements of the work—the suffering and the reward— the children only see the hard side of the work, the long hours, the glacial progress and associate it with suffering and nothing else. Think of an outsider walking into the gym when you’re nearing the peak of a high intensity workout—to them that voluntary suffering looks like masochism, but if introduced in the correct manner, the same experience can be bearable if not enjoyable. This farmer’s selfish (or perhaps simply careless) approach to advertising his vocation robs them of the very real joy of the work that in another life might have drawn them to happily follow in his footsteps.

Whether or not this observation is something the author was aiming to draw out is up for debate, but this is one of the things novels are capable of digging into that non-fiction has a harder job of doing. Through anecdotes, a reader naturally draws parallels to their own life, reframes things they thought they’d made up their mind about even if the topic matter of their life is miles from what they’re reading.

I’m a pathological reveller of suffering and “the work.” But I too often advertise it as something difficult. For the most part my writing regiment is a joy to dive into. It’s just setting the schedule and preserving that window of work that’s hard. For me exercise and training are the same. You drag yourself along to the gym, accept that what lies ahead is going to be difficult, then the rest is usually a joy. It’s the possibility that you might indulge an alternative to those “hard things” that tortures you.

This is true even outside of my “chosen” pursuits as well. Recently I started working for a furniture moving company to keep the lights on for my final few months in London. To an outsider this probably sounds awful. Manual labour? Lugging piano’s and what not up and down stairs, dealing with folks who haven’t quite packed before you arrive to help them move, driving a clumsy Luton van around busy London Streets?

But honestly, I’m loving it. It’s physical work, I’m around colourful characters who aren’t advertising themselves to be anything different than what they are, I’ve got lasting energy throughout the day, driving a manual vehicle around London streets is offering an entirely new perspective of the city than what I’ve had for the last two and a half years and my body feels capable of going into the gym more often than when I was working sedentary jobs.

Back in the day Orwell offered praise to physical work—

"The work of a man’s own hands, whatever its economic value, is the most genuine thing he can produce."

Hemingway likened his approach to writing to that of a labourer,

"Work every day. No matter what has happened the day or night before, get up and bite on the nail."

Even Bukowski — who wasn’t exactly known for a work ethic, had praise to lay,

"My ambition is handicapped by laziness. But there’s something about hard, physical work that can actually cleanse the soul — if you don’t do it for too long.""

—and while I’ll acknowledge I’m shamelessly putting myself in the same headspace as some of the greats here, I wonder if there is something to the writers’ mind and this type of labour. I know whenever I’m left to spend too much time inside my head, I’ll end that day mentally but also physically exhausted. Perhaps there’s something to the distraction, the simplicity, and the clarity of this way of passing time.

Okay, I’ve gone on a bit of a tangent here. But I’ll leave you with the song of another wordsmith, just to drive the point I’m trying to make home.