The rituals of a writer at work vary from the practical to the paranoid.

Some like bustling coffee shops, some need clinical silence; some tell themselves they need remote writing retreats to work, some perform best treating the craft like any other professional office role.

For the first year and a half of writing my novel, I exclusively listened to Tool albums. There was something about their mathematical, dark dives into the aural landscape of a bad trip that locked me into the atmosphere I wanted to capture in my writing.

The band didn’t make it easy for me however, as at that time Tool albums weren’t available on any streaming platforms. This forced me to find their music on Youtube which makes for a different listening experience. There’s no skipping tracks, you don’t get the same differentiation between songs, I went a long time not knowing the names of many of my favourite Tool songs as a result.

Which isn’t all bad. It requires a higher application of your own taste, it makes the rewards when you strike on the good bits feel a bit more organic.

They had their reasons for doing it: part artistic, partly autistic; that archetypal battle between the musician and the record label was undoubtedly emphasized by a strong case of bloated ego at both ends of the equation, all of which made them outliers of a different kind to what they already were. Which fits the brand.

But….

When their music was rereleased on all streaming platforms in 2019, the difference was visceral.

This band which I thought I’d become extremely well acquainted with in the two or so years that I’d been listening to them heavily, was introduced to me in a whole new way.

I wasn’t dealing with partial versions of songs, the quality was as intended. The track lists were ordered and laid out in the way the band had originally wanted, and the order of the albums were put in context.

Say what you like about that vampiric nature of record labels and the machine of the music industry, but bootleggers simply aren’t equipped to compete with the conveyor belt of time tested, sales stat certified processes that the industry has perfected over decades on the bones of who knows how many young musicians.

Which is a convoluted way of reaching my point.

Paywalls, harboring your art and rewarding those who support you.

All of these things make sense in principle. You want to give a little extra to those who have shown they care about what you’re trying to do. Those who are sticking around when times are dim, when the novelty has worn off and you’re trudging up hill eeking out what momentum you can.

For sure you want to differentiate these early supporters from the indifferent masses. You want to let them pass the velvet rope where the others can’t go. You want to show them they mean more to you than the ones who sneer at everything that doesn’t immediately compete with the red, yellow, green, purple flashes that are striking their synapsis from a 12 cm screen in scenes lasting 3 seconds or less.

This is a great argument for a personal paywall. You trickle some of your work free of charge to those who only care in a passive sense. If they develop a taste for what you’re bring to the table or at least want to support it, they are welcome to commit further by signing up to pay, and in turn you reward them with the premium tier of work you’re putting out.

And from the creator’s end of this relationship, if you’re clever you won’t make the price of entry too painful for them and incentivize more sign ups.

The comedian Louie C.K. proved the efficacy of this model when he was at the peak of his powers in the mid two thousand and teens by selling his comedy specials for $5 a pop on his personal website. This was a controversial decision during a pre-scandal stretch when he could have easily achieved the market norm of $25-$30 per sale by selling his content through the staple industry monoliths. People not only appreciated the gesture of the lower barrier to entry, they also gravitated towards giving money directly to the artist rather than forking out to the hangers on and parasites involved in distribution.

This resulted in a win/win both sales wise and audience good will.

Until I put some thought into this, I assumed I was on board with this version of the “Accessible” approach. Make it cheap, but still ask them to pay. But that was 2014. This is 2024.

Shifting trends and warring schools of thought.

These days the model for comedians has morphed further in the “accessibility” direction. Rather than the model of HBO, Netflix or Comedy Central, many are putting out their comedy specials for FREE on youtube. That’s how they give back to their fans—and somehow (via the cogs of a social media platform that I don’t understand very well) they make more money this way than if they actually sold their work.

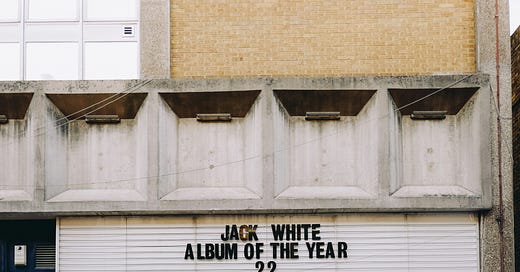

Compare this to Jack White of The White Stripes who put out an album last week that I not only wasn’t aware was coming out, but almost missed entirely because he didn’t make it available on streaming platforms. Instead he dropped it exclusively on vinyl.

Very Jack White.

But the thing is…by doing that he’s made it hard to listen to.

I’m right back to where I was with Tool. I can still find bootleg versions on youtube. But I won’t listen to it on the go. I’m not going to learn the names of the songs. I also have to deal with ads which hardly allow for the best listening experience.

Furthermore, I probably would have been willing to pay to get that album on my phone. It’s not for lack of loyalty to the artist that I’m not going to buy the vinyl, it’s practicality. I’m living overseas right now, I don’t have a record player here. That’s also not the way I tend to listen to music most of the time. I’m a headphones in, listening while I work, travel, exercise. I’ve never been big on sitting in the room, speakers turned up, letting everyone else hear what I’m listening to. For all his vision, I think Jack White is a bit old fashioned—and I’m sure he’s well aware of that and doesn’t care, which is respectable.

Respectable, but a bit annoying.

So how does this all apply to me and writing in general?

The other element to consider about every example I’ve used above is: These artists all have established audiences.

Does that buy them a freedom that isn’t available to nameless creative? Do you need the big five publishing deal, getting signed to Geffen records, having your two season series streamed on Amazon Prime, to launch you to X velocity before you can start thinking about the tactics above?

It’s hard to say.

As I eluded to last week. I’m increasingly warming to the idea of tilting the bulk of my writing here on Substack towards a free audience for the sake of getting eyes on the work. Sure there’s some pride tied up in doing that, “I don’t work for free,” but maybe that’s outdated? Maybe that’s not the way to get off the ground.

A big portion of this page is designed to display a trajectory of improvement— making a thousand imperfect chairs vs trying to sculpt one perfect chair. Am I muting an element of that effect by only making some of it available?

I appreciate there are some crossed wires in my logic here. On one hand I’m saying “the giants of the industry are the best at publicizing your work and making it accessible to the widest number of people,” On the other I’m saying “paywalls are bad, make it all available.”

It’s all an equation. Not one that I’m positioned to make a call on just yet, but I think it’s important to mull this stuff over all the same.