Tome: “a book, especially a large, heavy, scholarly one.”

Doesn’t hearing that word alone make you feel a little bit sleepy? Tome. Even the way it rolls off the tongue is dusty.

Definitely a great hook for the start of an article ay?

Maybe it’s just me, but even if I was told I only had to read one page of a “tome” my immediate thought would be, “this is going to be a slog.”

That’s why I’m terrified to have the term tome attached to my work in any way shape or form. Prior to my most recent revision, my novel was sitting at one hundred and twenty thousand words (which for reference is just short of five-hundred pages)

Even though the science fiction genre (which my work very loosely fits into) is known to run a little bit longer than your average paperback, as a debut novelist I’m fighting tooth and nail to cut my word count severely.

It’s tricky, because my setting is fictional which means a good chunk of that word count gets eaten up by worldbuilding. All the same, I’m treating the hundred K word count like it’s an off ramp from the getting-published-highway.

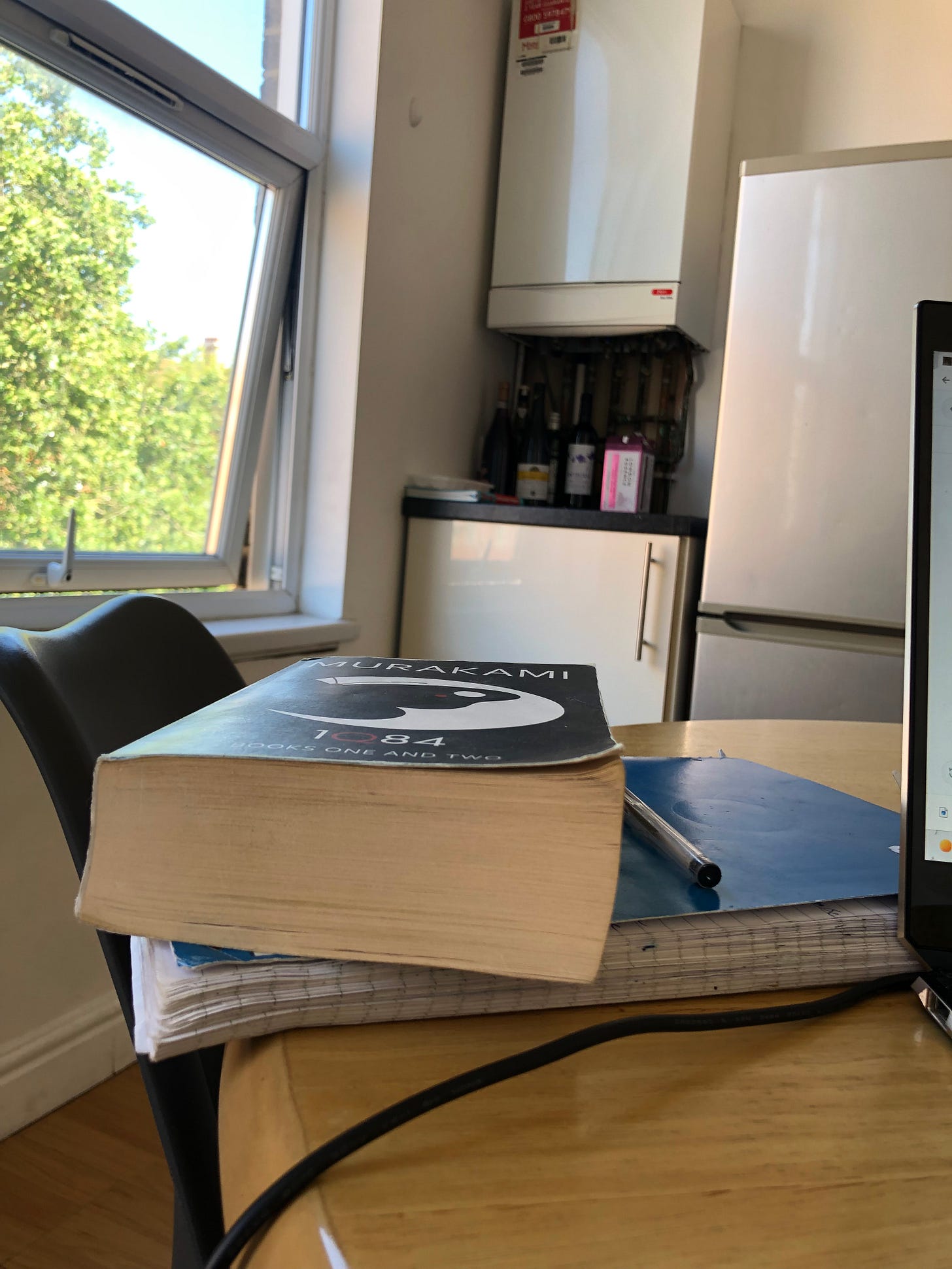

I guess this is particularly fresh in my mind because I just finished reading Haruki Murakami’s novel, 1Q84—which falls into the Tome category by my standards. It was recommended by a friend due to it’s parallels with my own novel—plus anything that’s referencing Orwell holds a special draw for me. 1Q84 boasts an eight-hundred-and-five page-count (and that’s not even the full series).

It’s not a good book.

No. That’s not true. It’s almost good, but it should be about three hundred pages shorter.

I guess at this point in his career Murakami’s earned the right be a touch self-indulgent, but man…the old adage “kill your darlings” is parroted by writing teachers for a reason. 1Q84 is full of plot threads that simply don’t need to be there and some pedophilia references which are hard to sit through. I understand the difficulty he faced in attempting to juggle a complex, high-concept plot while maintaining a very simple prose style, but it’s at the expense of the reading experience in my opinion.

I suspect Murakami fell into the trap that George Saunders talks about from time to time. The temptation to make one of your writing projects “grander” than it’s meant to be, to create that Magnum Opus, the sophisticated tale that’s going to define you as a great.

It’s the same temptation that had me staring at the ceiling in a half paralytic state when I was in Portugal. You should never let a story stretch for that type of grandeur unless it’s one hundred percent organic.

“Should.”

Who am I to throw out words like that? Obviously these is all my own unsolicited opinions, so take them with a grain of salt.

From my experience when you finally get the words down on that page, they never live up to the abstract thing you had in your mind—and that’s because that abstract has too many of your fingerprints smudged all over it by the time it comes out of you. You’re like a spotty kid at Bandcamp trying to channel Coltrane with your pudgy uncoordinated fingers.

The best you can hope for is that whatever butchered parody ends up coming out resonates with your readers by virtue of it’s relatability rather than grandeur. As far as I can see it, the most direct route to achieving this is by being honest with yourself about your own chops, recognizing what type of writer you actually are, and once you’ve got that figured out, approaching your readers with a shitload of respect.

That usually involves something short. Something heavily edited. Not a tome.

And I’m not preaching low standards here. If you genuinely turn out to be a great writer, this pared down version may still find its way into the halls of literary classics. But from where I’m sitting, for most of us that attempt at masterpiece is ironically a path to mediocrity.

The best stuff I’ve ever written comes in the moments where I’m trying to be concise and snappy, when I’m writing loose and not even thinking about being ‘deep’—whatever that means.

And this isn’t a condemnation of longer books. Last year I read Infinite Jest and The Brothers Karamazov. Both are pushing a thousand pages. Both were worth the effort.

I’ve retyped this paragraph three or four times, trying to pin down the point of difference (and I suppose the point of this article) that places these two books in a different category to 1Q84, but can’t really put my finger on it.

I guess as with all things art, this topic is subjective. I just feel the latter two books justified their length with the depth of subject matter and the pervading sense that they had already been through strenuous cuts to get down to this length. They couldn’t help but be this long.

Then again, David Foster Wallace and Fyodor Dostoevsky are two of my favourite authors, Murakami doesn’t speak to me in quite the same way. Maybe I’m just playing favourites.

So what is my point here?

I guess it just comes down to understanding what you bring to the table as a writer. Have you earned the right to ask your readers to take on a six hundred pager? J.K Rowling managed it on book four of the Harry Potter series, and that was for an audience of children. I can still remember the thrill of opening that thick paperback—dragon on the front, the first book I’d tackled with a proper dustcover—there wasn’t a glimmer of intimidation.

But that’s a unique case I think. To present a reader with a tome, you are asking them to spend a shitload of time in your head. Aside from the ‘smart person’ points a reader gets from being seen with a dictionary-thick novel in public, you’ve got to make sure you’re rewarding them with something that makes the effort worthwhile.

On a side note: I read the Brothers Karamazov on a kindle. I don’t recommend it at all. No matter how much you want to tell yourself it’s about the content, not the race to finish. I’ve got to admit, there’s a little thrill in seeing your book mark track its way through one of those doorstoppers. Anyway, now I’m rambling at this point. Come back next week for the final instalment of A Handshake with Rollo.