Cult /kʌlt/ noun

1.

a system of religious veneration and devotion directed towards a particular figure or object.

"the cult of St Olaf"

2.

a person or thing that is popular or fashionable among a particular group or section of society.

"the series has become a bit of a cult in the UK"

“I’d never join a cult.”

That’s a funny sentence to say isn’t it?

Because it implies that there’s someone out there who might say the opposite.

If you take less than five seconds to think about it, it almost seems like there would be. People do join cults after all, so it only follows that if asked, they might say the words—

No. If you knew it was a cult, of course you wouldn’t join. Do you think the people in the Moonies knew they were being manipulated? No, their attention was pointed outward. Coached by their peers, they kept their focus on the people pointing unsolicited fingers at them, telling them, “you’re a brainwashed fool,” and with no shortage of justification, chose to believe those people were the ones attempting to manipulate.

Can you blame them?

After all, they chose to be a part of this group. They’ve got memories of volunteering to join. They remember the the joy of being accepted.

The same goes for pyramid schemes, manipulative sub-cultures and predatory employment situations. If you think you’re going to convert these members by telling them how dumb they are for being sucked in, you won’t get very far.

No one signs up for the nightmare version of these groups. They join the shiny brochure version—usually when they’re at a low point in their lives. At a time of desperation.

The saddest part is, they often don’t find out they’ve been sitting on a slow boil until their skin is peeling from their flesh.

Why am I talking about this?

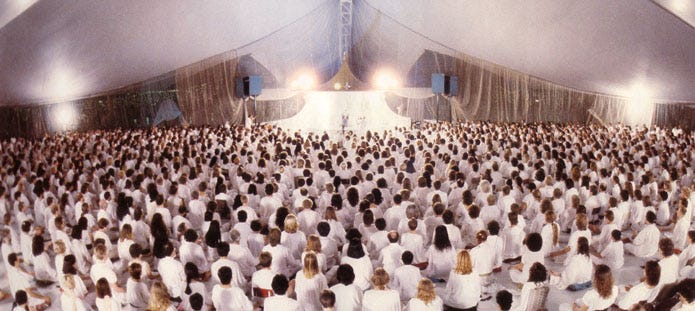

I can’t say I’ve ever been part of a cult myself.1 You’ll never see me doing evil deeds for Charlie Manson, moving to the desert to be close to Osho, spending my life savings to discuss thetans with Tom Cruise. So what qualifies me to discuss what can often be a family destroying topic?

I’m a member of society.

No, I haven’t brushed shoulders with the most extreme figureheads of this phenomena, but I have had my fair share of dealings with lower grade versions of it. Most likely, so have you.

I’ll be careful here to differentiate ordinary coercion from undue influence, because they’re not the same thing. Influence in daily life is impossible to avoid, and most of the time it’s not a nefarious thing. The point where it crosses over, is when the person applying it intends to take something, or make you do something that you otherwise wouldn’t have done—and will likely later regret.

Now my radar for this stuff might be slightly more sensitive than most due to the topic matter of my novel, but if you’ve got your eyes open, you can see versions of it everywhere.

These types typically target people who are going through times of liminal change, university students, divorcees, people who have recently been made redundant, people who have had a death in the family, new parents.

Which is another reason I’ve got an outsized radar for this stuff. While thankfully none of the above situations describe me. Over the last twelve months, I’ve positioned myself in a similarly vulnerable state to this type of manipulator, of a kind that is uncommon for people of my age group.

I separated myself from a stable social circle. I shed my former career identity and left all that comes with that in another country. I’ve been actively joining new groups (writing related). Going alone, consciously attempting to keep an open mind. Meeting new people. Actively chasing an unstable pursuit that has no clear road map. And more recently, I’ve stretched my financial resources further than I intended, and found myself in a job market that’s offering more rejection than affirmation.

Sure I like to tip-toe along the edge of chaos from time to time, and more often than not, it’s been my curiosity rather than necessity that’s kept me in the room with these manipulators after I’ve identified them. But it’s not difficult to project how slippery things could get, if I added a few more variables to the above list, and took away a layer of my own healthy paranoia regarding these people.

So who are these “ordinary” manipulators?

I’ve already touched on a couple of these in previous articles.

One: The thinly veiled “writers’ group,” that was clearly designed solely to recruit new followers for their pseudo-psychological ideology. These people demonstrated so many of the coercive control tactics I’ve read about. Using planted “outsiders,” social proof as a means to build authority and undefined timelines to destabilize the new members. These people sucked me in for four hours one Sunday afternoon, even after I’d identified what they were. I’ll write a more detailed account of this in the months to come.

Two: The writing retreats and workshops which position themselves as opportunities to learn, but in reality are more focused on selling the “idea of” the author’s lifestyle cosplay that doesn’t actually get it’s clients any closer to their goals. (More about this type here).

Granted, this is a softer form of coercion (and really can be put in the same pool as manipulative advertising) but I’m including them here due to the baseline dishonesty of their message. If a participant knew that they were signing up to a sort of short term fantasy and was willing to pay for that experience —that’s fine. It’s the categorization of these things as some valuable jumpstart to a writing career that rubs me the wrong way.

Three: My most recent encounter—and one I haven’t written about on here yet—a commission-only, real estate business that not only offered zero pay to it’s employees, but required them to front a monthly fee for the privilege of working for them.

I’m not joking on this.

This company required its employees to pay an upfront fee of 750 pounds (which bought you a day in the studio to work on your “personal brand”) and then an additional 250 pounds on the first day of every month.

The first red flag arose, when instead of a standard job interview, the hiring manager presented me with a video seminar. This was explained as “the easier way to manage things due to an overwhelming number of applications)

Once again, I realized I was a part of a scam pitch early on, when the salesman started by talking down “traditional” agency models, and positioning commission only as the way of the future. He told an outright lie saying, “the UK is decades behind other countries like the US, Australia and New Zealand, who have exclusively moved on to commission only.”

I guess he was banking on nobody being fromone of those countries? Or having access to google?

In any case, this was the tone of the entire pitch: talking down alternatives in order to build up his offering. He name dropped football players, middle eastern princes and celebrity clients, all to build authority and make it feel like he was offering his employees an opportunity to be part of an exclusive social sphere.

He justified the costs by pointing out how many overheads a prospective agent would have to front if they started their own franchise.

Bear in mind, he’s talking to an audience of first time agents—people who are nowhere near the position of franchising. These are simply desperate people looking for a job, looking to learn.

“Until you’ve built up your client base, you probably won’t be bringing in any money to the company,” he, “so these fees only represent a small portion of the costs we’re covering for you.”

The guy was using classic manipulative coercion tactics—ones that I’ve actually used in my novel. Placing the burden of results on the “employee,”

If they fail to make a sale—they haven’t tried hard enough. They’re not hungry like other salesmen out there. They’re not making the most of this opportunity. They’re wasting the fees they’re paying. “Do you even want to be here?”

A lot of guilt. A lot of shame. But not a lot of practical tools to actually help those employees reach the success they’ve been sold—Their revenue stream is based on these signup fees and these monthly “overhead” payments after all, so why bother investing in that?"

And let’s say, the company strikes gold with an employee who somehow manages to spin some genuine clients from the sparse conditions they’ve been offered?

Great. The company takes a cut, this employee becomes a model for their next sales pitch and the cycle continues.

Why is this important?

I realize this article has wound down a road that is quite far from the pursuit of getting a novel published, but I think it’s important to demonstrate the parasites that are waiting along the way to exploit people with idealistic visions of the future. Chasing a dream put’s you into a place of vulnerability, and it makes me angry to see people taking advantage of that.

The worst part of that sales pitch wasn’t the insult to my intelligence, that this sleezy, unimpressive man thought he could suck me into his exploitive scheme, it was the use of one of his victims as part of his pitch.

A poor guy named Marcin, a recent Polish immigrant—roughly in his forties— called into the “seminar” from out on the street (still knocking on doors at 8:00 at night, to “build his client base”)

He explained that he’d been working for this company for a week, he did his best to sound positive, but his pitch was clumsy and visibly aggravated the con-man running the seminar. The guy immediately dressed him down and made fun of his accent saying he sounded like Arnold Schwarzenegger—which he concluded was the reason for his lack of success so far.

It was hard to sit through, and I don’t even want to think about how that poor guy was paying his fees. He likely moved to this country, hoping to find more opportunities and was faced with the tricky reality of the current employment market. This scumbag was waiting to sweep him up. It’s criminal.

Anyway, I’m probably a bit too close to this topic to say anything objective about it. I won’t name the company or the scumbag running it, because that’s not really my point.

This company represents the low-level extortion that goes on beneath the surface of our society every day. They’re not extreme enough to make headlines and capture the attention of the public, but they use the same tactics and principles that cults do to deal out damage—and by virtue of their “ordinary’ camouflage they probably affect a broader sample of society than their flashier counterparts.

So I’ll ask the question again.

Would you ever join a cult?

Although some might argue that the Jiu Jitsu community ticks a few more boxes on the cult checklist than you might think.