Disobedient Stories and the Shadow Playing Up

If you’ve been paying attention to this page at a level of detail I can’t reasonably expect from anyone, you may have noticed my most recent story, Axolotl Park, covers very similar ground to “Britney’s Mushroom, one of my earliest stories on here.

Both follow a judgmental, slightly cynical narrator. Both characters encounter an outsider and ply judgement, before the story culminates in some form of retribution for the narrator in question. Either externally or internally.

In neither case are you meant to be on the first person narrator’s side. I’ve written both in a way that will hopefully wedge a distance between the reader and this outspoken voice.

Despite the obvious parallels between these two short stories, I wasn’t setting out to write thematically on either Axolotl Park or Britney’s Mushroom—and I certainly wasn’t setting out for those themes to cover the same ground. As I’m discovering more and more however, these things have a way of elbowing their way in whether I like it or not.

The Swiss psychologist Carl Jung, would probably have had a lot to say about why this recurring idea has crept back into my work almost twelve months on.

My subconscious leaking into the writing perhaps? Unaddressed thoughts given voice through my characters?

I’ll come back to this point in a moment, but first I want to explore this train of thought via another example.

Brief Interviews with Hideous Men

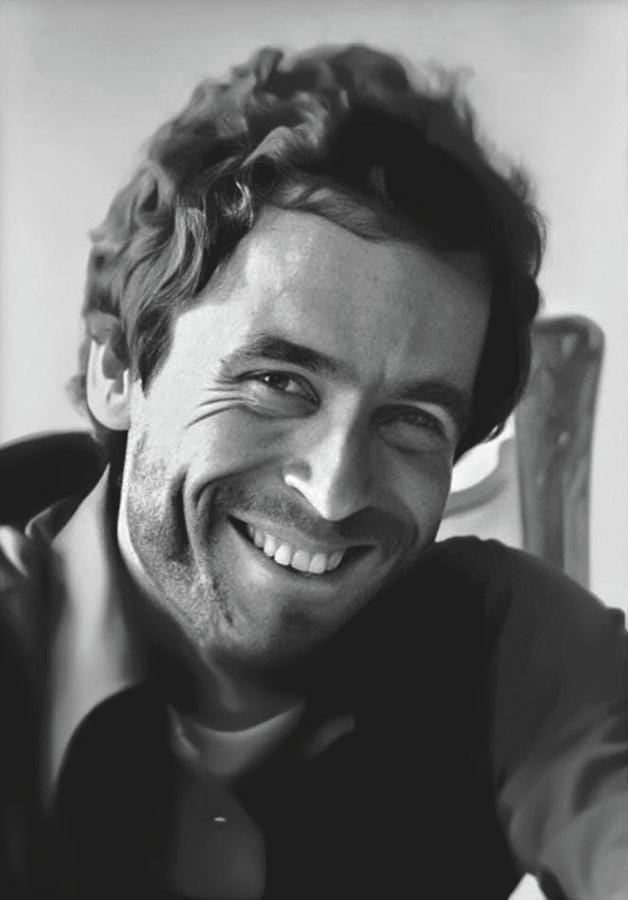

Behind the paywall, I recently wrote a newsletter about the author David Foster Wallace, briefly touching on his post-humous recasting as a misogynist by people in the literary world.

While I’m adamant on maintaining as much distance from these culture war discussions as I can. For the services of this topic, let’s assume the claims laid against him are all objectively true.

Let’s assume he was a misogynist.1

This suddenly injects his 1999 short story collection, “Brief interviews with Hideous men,” with an extra dose of complexity.

The premise of this collection is in the title. This book consists of a series of interviews or short vignettes focusing on a man who is pre-framed as a capital B, Bad person. In his signature post-modern style2, DFW’s interview sections omit the unseen female interviewer’s questions entirely. Including only a “Q” and leaving the reader to decipher the content of the question based on the interviewee’s answer. Giving voice solely to the men she’s interviewing.

The whole thing is a very on-the-nose3 judgement of the subtle manipulations men will engage in while in relationships and in general life. A topic that could easily get very political and—let’s be honest—boringly didactic if that’s as deep as the story runs.

But the mastery of this collection is in the relatability of the characters. DFW gets you on board with their POV a lot of the time. These aren’t strawmen monsters. They’re often likable and clever.

You’re meant to feel a little tug of guilt. A brief, “Shit, he’s kind of right about that one,” before you’re reminded of the framing. “No, this is a “Bad” guy.”

This all has the effect of leading the reader to judge, not just the characters, but to also judge themselves, judge how easy it is to be complicit in these fictional (or not so fictional) instances and consider, “hmmm maybe this is a complicated topic. Maybe there’s some nuance to all this stuff.”

During press interviews promoting the book, David Foster Wallace openly admitted that some of the conversations he included in there were ones he’d had personally had with romantic partners in his own life.

So you’ve got to assume he probably was guilty of misogyny in his own life, and aware of it. But equally, it wasn’t something he was proud of. To think we’ve all got rock-solid dominion of our own traits is naïve.

Now before this starts to read as some type of apologist piece, let’s get back to the point.

The Shadow

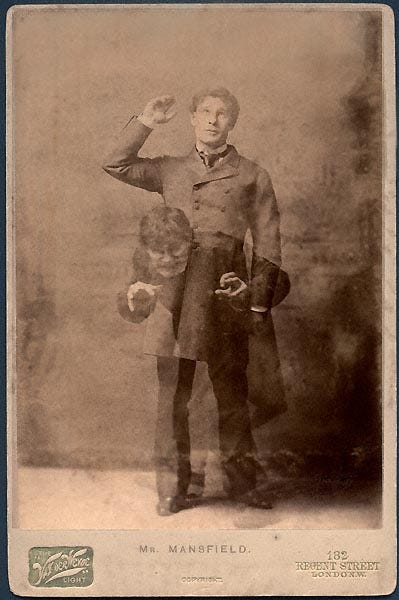

Carl Jung, and a concept he coined called The Shadow.

In a butchered nut shell, Jung claimed we all come into the world with a set of personality traits that are hardwired. However, when we begin interacting socially, we realize not every trait is received in a positive manner by our peers. Maybe we are too cocky, and it’s annoying to others. Maybe we’re a bit over aggressive and other kids stop wanting to play with you because of that.

When faced with these reactions, anyone with a sound head on their shoulders will self correct. They’ll begin to develop a persona built around the positive aspects of their personality, not letting other people see the negative traits whenever they can help it. The problem is, people tend to stop letting themselves see these negative traits as well. They push them down and convince themselves that they’ve moved on.

But these traits never truly disappear. In fact, if given no room to vent, they grow and become something a person can’t control.

Don’t we all recognize people like this instinctively? The buttoned up golden boy, who is just a little too clean. I can’t help but get my bristles up slightly when I’m faced with someone like this. “Where are your demons? Why don’t I see any fraying threads. How many bodies are you hiding under your floorboards?”

An exaggerated example of this is the archetypal, holier-than-thou preacher, who publicly admonishes homosexuality , but secretly hires male hookers late at night.

Serial killers with a specific “type” are probably manifesting this phenomenon as well.

You hate the “flaws” in others that you recognize in yourself.

Jung’s theory is, you should channel your shadow in healthy ways. Embrace them as a part of you and integrate them into your personality in ways that won’t repel.

So bringing all of this back to DFW and my two similarly themed stories.

The Expression of the Shadow

Is it possible that these themes popping up in an author’s stories are a recognition of things they’ve buried beneath their public facing persona?

If I was asked very quickly what the shared message of Axolotl Park and Britney’s Mushroom are, I’d probably say something along the lines of. “Don’t assume you’re better than the outsider. Don’t assume they ended up on the fringes because they failed at the conventional way. Maybe these “outsiders” chosen to take a different path because they’ve rejected the standard way of doing things.”

This is a position I’m comfortable taking. It aligns pretty well with my persona. I’d publicly stand behind it.

Why does it keep recurring in my stories then? As if I feel I haven’t quite resolved the point I was trying to make, even though both stories cover this ground pretty comprehensively?

What if it’s something else. A lesson to myself—courtesy of The Shadow?

At the risk of turning this into a therapy session, I’ll cut the personal reflections short here.

To use my other example, is DFW embodying the enlightened post-modern writer as a way to say to himself. “Look Dave, you know this isn’t a good way to act. Give it a rest ay?”

If so, this begs the question: if this is a case of the shadow attempting to communicate with the writer, would this use of stories even constitute channeling in a “healthy way?” Or is this leakage just a symptom rather than a cure?

Does it Work?

DFW is hardly doing the equivalent of an ex-con whose changed his violent ways by taking up martial arts, here. Once that story is written, I can’t imagine it bottles up all those subconscious demons and stores them there like a genie.

DFW struggled with drug addiction when he was young, battled with lifelong depression and eventually committed suicide, so his internal demons almost certainly stayed with him until the end. If “Brief Interviews with Hideous Men,” was an attempt to exorcise some of his acknowledged, misogynistic tendencies, to let the shadow breath for a while, I’d hate to find out what else was lurking beneath the surface of his mind.

But maybe this is all too literal. I doubt anyone can really draw an accurate cause and effect from thoughts to action. Particularly actions this extreme.

As far as I can tell, psycho-analysis of this kind4 is only helpful to a point, and probably less so when applied from the outside looking in. It’s interesting to ask the questions though.

This all ties into the mystery around where ideas come from. What compels you to take a story in a certain direction? Questions that don’t seem to have answers even in the minds of the people creating the art that these ideas result in.

This is hardly a leap as the man all but accepted this label himself (albeit referring to his capacity for misogyny rather than claiming the constant state as a badge of honour)

A literary style that is self-conscious by design. Drawing attention to itself as a piece of writing, through the use of structural choices, such as footnotes etc.

Dare I say feminist?…..

Particularly when attempted by someone with a surface level knowledge such as myself.